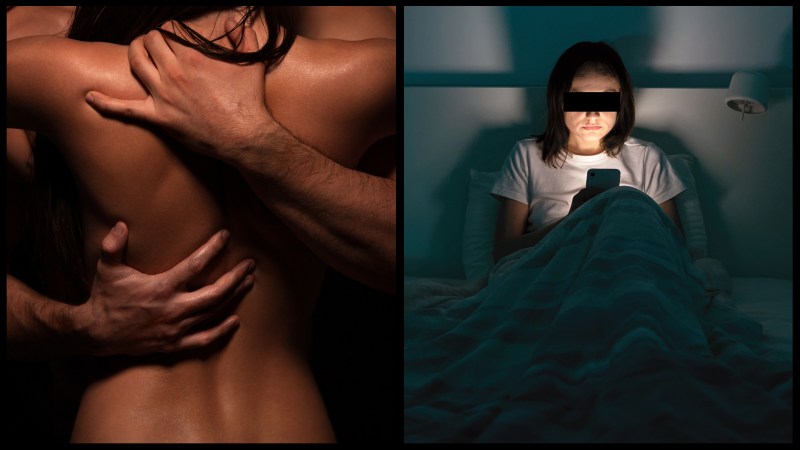

I stared at my face in a sex video. I was a deepfake porn victim

I was in my third year at university when I clicked on the link a classmate had sent me and plunged my entire life into freefall. “I’m really sorry, but you need to see this,” his message said. It was a link to the Pornhub website. My first thought was that his account had been hacked, but he said, no, it’s genuine. So I clicked, and immediately my face popped up on the screen.

• Taylor Swift fans’ fury over ‘appalling’ explicit AI pictures

I was now staring at my own features in a porn video, making direct eye contact with… me. It was surreal. What was this? I was confused. That wasn’t me, yet it looked exactly like me. This person who looked like me had a user name that was mine, a photo that was me, and had a profile that included my home town in the US and my university. “DM [direct message] me if you wanna get personal,” it said. I had been getting some weird messages from guys on Instagram recently (“You’re hot”; “I’m local”) and suddenly it clicked — they’d seen me on this porn site.

There were six or seven videos, all with at least a couple of thousand views. They had titles such as “Taylor Klein tries porn for the first time” and “College brunette exploited”. I also found an account in my name on another porn website, xHamster, again with all my details, which had disgusting comments underneath (“I live nearby, let me f*** you” and worse).

After the initial confusion, there was terror. These people knew my face, they knew my name and where I’m from. It’s not a big town, so it wouldn’t have been difficult to find my house. I was staying with my boyfriend when it happened and I told my parents the next morning. Like me, they’re both computer engineers and they researched it too so they could help me get to the bottom of it. Back then, in May 2020, none of us really knew what a deepfake was — my classmate who’d sent the link explained that it’s when images and videos are digitally manipulated to make it look as though someone is doing or saying something they’re not.

These days, it’s estimated that the number of deepfakes doubles every six months because the technology is advancing so quickly. Deepfake porn is big business, and what happened to me continues to happen every single day to women around the world. For that reason I agreed to feature, anonymously, in a documentary about my case. My name is not really Taylor Klein, and the face you see in the programme is not really me — it’s an actress. In a neat piece of symmetry, the documentary-makers used the same deepfake technology but turned it the other way: my face on someone else’s body in the porn videos, but my body and an actress’s face in the documentary. So it’s me you see in the interviews and video diaries, but also not me. It’s pretty badass.

When it first happened, I thought the police would investigate and this might all be over quite quickly, but I was told a crime hadn’t been committed, which seemed insane. A detective was assigned to my case but, when he called, his first question was, “What have you done to cause anyone to do this to you?” It was unbelievable. Somehow this was my fault?

I was constantly chasing them for updates, but in the end they spelt it out: whoever did this didn’t break any laws. It’s gross, but they technically had a right to do it. I was not a “victim” in the sense of the non-consensual pornography laws, because it was not my body in the videos. They could possibly pursue this person for impersonating me online, but making and sharing deepfake videos was not illegal. As I’ve since found out, this was the same in many US states, and as far as I know it’s still true in my home state. There’s no federal law, and an executive order on AI signed by President Joe Biden in October 2023 draws attention to deepfakes, but doesn’t outlaw them.

In those first days and weeks I became very paranoid. Who had seen these? Would those people who left such creepy messages come to find me? It was all-consuming. I spent a lot of time in tears. I was scared for my safety every time I went out. This happened in the early days of Covid, when everyone was frightened to leave their house, and this became another layer of scary for me. I had always struggled with OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder) and anxiety (I was the girl who was stressing about getting into college aged 12) and this exacerbated it. I’d check the oven was off, the doors were locked, my car was locked. Repeatedly.

I remember sitting in class one day and wondering how many people in this room had seen the site or who knew about it and was just not saying anything. Did they realise I didn’t make the videos? That they weren’t real? I have always been someone who cares a great deal about how others perceive me, and whoever did this had destroyed that. As the weeks wore on, the initial fear for my physical safety subsided a little and I began worrying about my future: potential employers doing background checks; job applications. I pulled back from my college friendship group and became a lot less trusting, a lot less visible online. It was such an isolating experience.

I couldn’t unsee those images; they were on my brain all the time. I became fixated on who had done this and why and realised I would have to conduct my own investigation. No one out there was going to do it for me.

It was by coincidence that I found Julia. Her boyfriend and I were in the same chat group and one day he mentioned deepfakes. I thought he’d heard about mine, but it turned out he meant that his girlfriend had been deepfaked. I made contact with her and we realised we knew each other. We’d lived on the same floor in our first year of college — two girls among a ton of guys in engineering.

Immediately, I felt I was getting somewhere. Before, it could have been anyone in the world who had done this. I may never have found the answer. But now we knew it had happened to both of us, it had to be related. It had to be the same person. We video-called each other and came up with a shared list of people who could have had a motive. People we both knew who had expressed violence against women in their social media or who had gone really deep into the dark corners of internet culture, plus anyone we’d fallen out with or had a disagreement with.

It didn’t help that casual sexism is so normalised in men who are into deep internet culture — and within Stem (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields too, because women are so outnumbered. In my class there were two women to roughly fifty men. Guys have acted creepily towards me in class; I’ve been heckled. There were always jokes about porn and about women. It’s hard to stand up to that when there are so few of you. No one wants to be the one who “can’t take the joke”.

However, we managed to narrow it down to three people and then the hunt really began. We spent hours scouring the internet. We reverse-searched images — there had to be something out there.

Our luck changed when we were on 4Chan, an anonymous forum where you can post anything — like Reddit but much, much darker. On certain 4Chan threads users would post a picture of a woman and ask for things to be photoshopped onto it, like semen, or they’d ask others to post images of women. Other users, clearly deepfake content creators, would offer their services.

After a lot of delving in dark corners, we found a picture of a woman we both recognised from college. Then another, then another. Once we found them it clicked —they all knew Mike, one of the three suspects on our list. He was on our course and he’d lived on our floor, and I’d lived with him again in our third year. He and I had been very close friends, but towards the end of 2019 we fell out. He’d struggled with mental health issues and I had always tried to be there for him. I advised him to see a doctor or therapist but he got pretty intense and I felt overwhelmed. I barely had time for my work because I was spending so much time with him. One day I lost it and lashed out, telling him to leave me alone, and we didn’t really speak again. Julia had a similar story.

As far as we could see on 4Chan, all these pictures came from a user called Krelish. After more searching we found a website called MrDeepFakes, completely dedicated to making and sharing this kind of content. This same user had posted tutorials on how to make deepfake videos, which looked almost like a lab report. They had 1.6 million views. We were now 98 per cent certain it was Mike.

Around the same time, we found a photograph of Julia on a 4Chan thread that we recognised immediately. We could both pinpoint the exact moment it was taken: on Mike’s birthday, in Julia’s room, when she’d made mimosas to cheer him up. It was such a personal photograph. It wasn’t on social media, and the only person who had access to it was Mike.

It sounds odd, but there was a kind of relief in knowing with some certainty who had done this to me. Sure, it made me angry — incredibly angry — but in a weird way it made me less nervous. It wasn’t a random stranger wandering around my town out to get me.

By now it was November 2020, six months after I’d first seen the videos. I really wanted justice, and figuring out it was Mike gave me renewed energy. Julia and I had found photographs of other women who had been victimised and we passed everything to the police. Now, at last, we thought we had a path forward to get something done.

But it turned out that Mike had always used a VPN — a virtual private network — when he was online. It concealed his IP [computer’s] address so he wouldn’t be traceable, so the police could not definitively link him to making and sharing deepfakes. I had the last follow-up call from the police, who closed the case with a breezy, “OK, we’re done.” That was a very low moment. After all this, we were going to be denied justice?

I’d already given the police Mike’s details and it turns out they called him; his mum had picked up the phone, apparently. They told me that during the call he didn’t admit to doing it, but he didn’t deny it either. They told him, “This can’t happen again,” and he was like, “Yep, OK. It won’t happen again.” At the end of the call he actually thanked them for their handling of it. That still rankles: the fact he thanked them meant he knew he had got away with it.

It’s infuriating. I’d had to leave my college friendship group. My life had changed for ever, my reputation had been tarnished, and somehow his was fine. It felt like I was having to deal with all the consequences that he should have had to deal with. I was so tempted to post on my social media what had happened and to warn others to be careful. But I worried that I would be committing slander, because at this point it was his word against mine. I don’t know if that was a rational fear, but it’s all part of the silencing of victims that comes in cases like mine.

We don’t speak out, because we fear it will trigger the person to do this again. We also worry that highlighting it will send people off to look for those videos. Women who do speak out often have to contend with disgusting messages and harassment. I don’t want this to follow me throughout my life. I’m now 25 and working as a hardware engineer in the Bay Area in California. It’s the life I always wanted for myself. In the documentary I’m able to share my story in a pretty safe environment, but if I were to connect my real name to it, people at work could ask about it. I would never be able to escape.

As word got around, Mike was removed from a few group chats, but I still don’t know how many people at college knew it was him. As far as I know the Pornhub and xHamster profiles have been taken down, but there’s always a fear that there are more videos out there that I haven’t seen.

It’s becoming easier and easier to make a deepfake. During my “case”, it was thought you needed about 150 pictures of someone to make a deepfake video — not difficult to find if you use social media. The more pictures the deepfaker has, the better likeness they get, because there are more data points for the AI to learn from. However, I believe you can do it with fewer pictures now, and the accessibility of the tech has dramatically increased — anyone can now put pictures straight into an app or program and they will be mapped onto a video with AI, using data points from the pictures to recreate your face. It seems that Mike wrote these programs himself, but at this point it takes very little effort for anyone to do what Mike did to me. That’s so scary.

There are now more than 9,500 sites that specialise in non-consensual imagery, and the biggest deepfake porn site averages 14 million hits a month. There’s a misconception that it only happens to celebrities, that it doesn’t happen to regular people. But it absolutely does.As told to Rachel CarlyleAnother Body: My AI Porn Nightmare is on BBC4 and iPlayer on February 6 at 10pm

Deepfake porn: the fightback

In the early days of deepfakes, when they still required considerable tech skills, explicit deepfake imagery mainly involved celebrities. Natalie Portman, Emma Watson and Scarlett Johansson were all victims. Now Taylor Swift is reportedly considering legal action over pictures posted on Twitter/X last month. It’s estimated that 96 per cent of deepfake videos are pornographic.

In the UK it’s now illegal to share or threaten to share deepfake content under the Online Safety Act, which received royal assent on October 26 last year. It is punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment and/or a fine. However, it’s not illegal to make deepfakes, which worries legal observers. The act, which covers all residents of the UK, should make it easier to investigate and prosecute deepfake offences, says lawyer Mark Jones, a partner at Payne Hicks Beach. “It remains to be seen if it acts as a deterrent. We won’t know until we see the kinds of sentences courts impose,” he says. Plus, if the creator lives outside the UK (which the vast majority will) the new law is unlikely to apply to sexual or intimate deepfakes.

The act places a duty of care on online platforms to remove illegal content, wherever in the world they are based. “It’s not a means of getting justice but it will make it easier for victims to get images taken down,” says Jones, whose firm represented Love Island star Georgia Harrison in her successful civil case against her ex, Stephen Bear, who uploaded intimate footage of the couple to the OnlyFans website. “Even though we won the civil claim and there was a successful criminal prosecution, it was difficult initially for Georgia to get the videos removed from online platforms. The act shifts the balance — there’s a legal duty on those platforms to remove illegal content or face a fine. Time will tell if this works.”